Spinal cord injury remains one of the most challenging areas of modern medicine. Despite decades of research, treatments capable of restoring meaningful movement after paralysis have been limited. However, clinical research emerging from Japan continues to suggest that stem cell science may be approaching a turning point.

In early 2025, researchers led by Professor Hideyuki Okano at Keio University reported early results from the first clinical trial using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells in patients with acute spinal cord injury. In the study, one previously paralysed patient regained the ability to stand and is now undergoing training to walk again, while another showed partial recovery of arm and leg movement following a single injection of reprogrammed stem cells. While these findings do not yet represent a cure, they offer important insight into how regenerative medicine may change future treatment pathways.

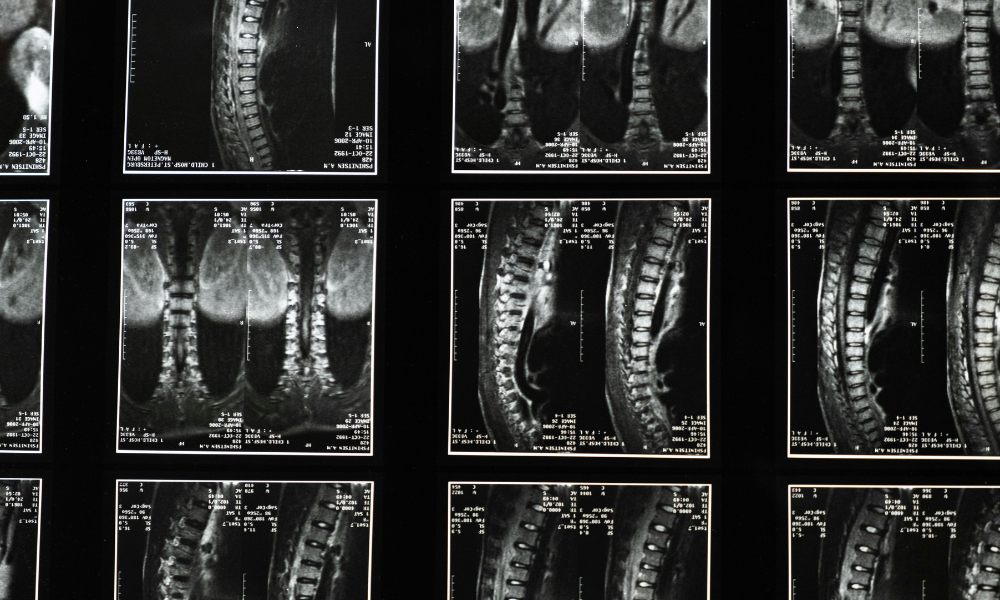

The trial involved four men over the age of 60 who had experienced severe spinal cord injuries two to four weeks prior to treatment. Each patient received an injection of two million donor-derived iPS cells directly into the site of injury. After a year of monitoring, researchers reported no serious side effects, including no evidence of tumour formation, which has historically been a concern with pluripotent stem cell therapies. Two of the four patients demonstrated measurable neurological improvement, suggesting that the treatment may be effective in a subset of patients.

Induced pluripotent stem cells differ from earlier stem cell approaches in important ways. First described in 2006 by Nobel Prize-winning scientist Shinya Yamanaka, these cells are created by reprogramming ordinary adult cells, such as skin or blood cells, back into a flexible stem cell state. Once reprogrammed, they have the potential to develop into many different cell types, including nerve cells and the supporting glial cells needed to repair damage within the spinal cord.

This flexibility gives induced pluripotent stem cells significant advantages. They avoid the ethical concerns associated with embryonic stem cells, can be produced in controlled laboratory conditions, and may reduce the risk of immune rejection when carefully matched. In the Keio University study, the goal was for the injected cells to replace or support damaged nerve pathways, helping to restore communication between the brain and the body below the injury site.

Before reaching human trials, Professor Okano’s team demonstrated similar regenerative effects in animal models, including primates with spinal cord injuries. These findings, combined with rigorous safety testing, led to full regulatory approval for human studies in Japan in 2019. Since the first patient was treated in late 2021, researchers have focused not only on improvements in movement, but also on long-term safety, an essential step in translating stem cell science into real-world medicine.

Previous attempts to treat spinal cord injuries with stem cells have produced mixed results. Trials using bone marrow cells, muscle-derived cells and embryonic stem cells have often failed to deliver consistent or meaningful recovery. As Professor James St John, a translational neuroscientist involved in spinal cord research, has noted, many approaches have struggled to work reliably across different patients and injury types.

The current findings suggest that induced pluripotent stem cells may offer a more adaptable and biologically effective approach, but important challenges remain. Every spinal cord injury is unique, and it is unlikely that a single treatment will work for all patients. Larger clinical trials will be needed to determine which types of injuries respond best, how soon after injury treatment should be given, and whether stem cells should be combined with rehabilitation, electrical stimulation or other therapies.

For the millions of people worldwide living with spinal cord injury, even small improvements in movement or independence can have a life-changing impact. While this research does not yet redefine standard treatment, it represents a meaningful step forward. Stem cell therapies, particularly those using induced pluripotent stem cells, are moving steadily from experimental science toward practical medical application. The coming years will determine whether this early promise can be translated into widely available treatments that restore function, mobility and quality of life.

Back to News + Insights